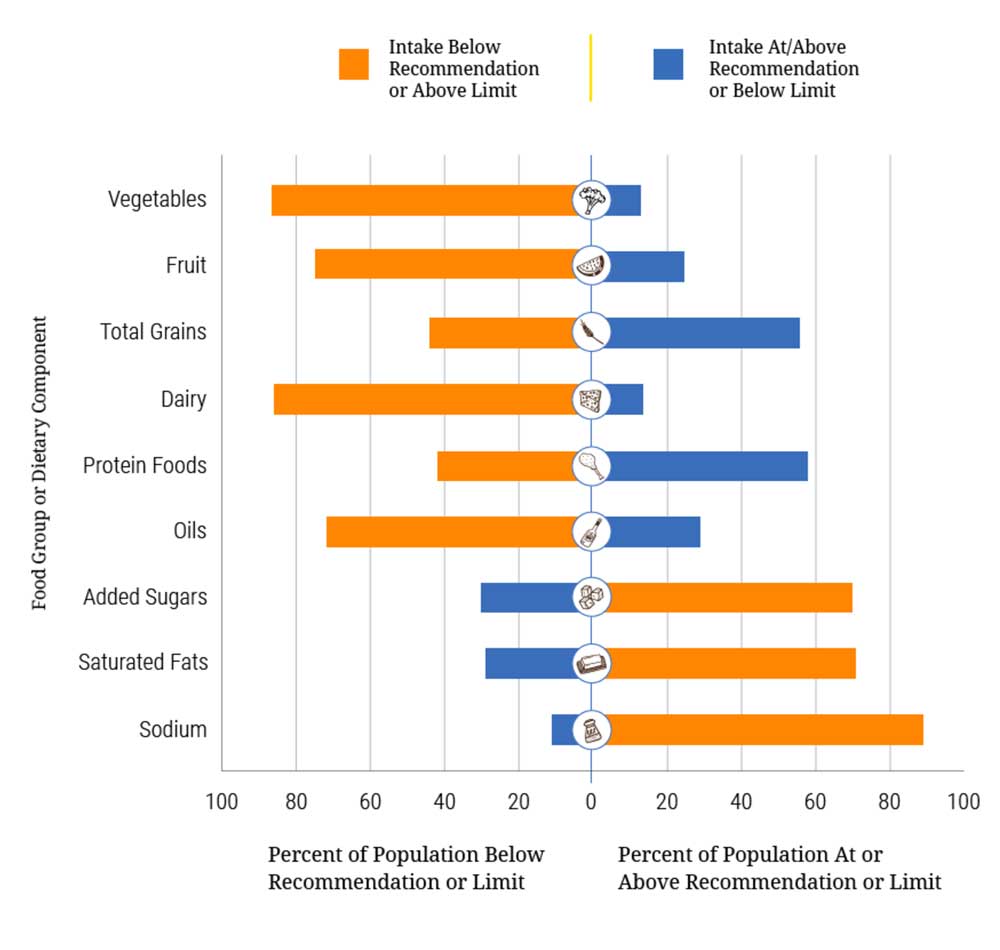

The typical eating patterns in the United States fall short of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines.1 Shocking, right? Once again, the Standard American Diet (SAD) reflects a nation that is overfed and undernourished.

Since the 1960s, the availability of chemically preserved and processed foods and beverages has steadily increased. As such, the Standard American Diet, heavily skewed towards unhealthy fats, excess sugar, sodium, and calories, is a recipe for compromised health.1

Are these nutritional deficiencies and excesses affecting your patients and your practice? Do you know where your patients lie on this spectrum? Should you be concerned?

First, consider the growing evidence for the associations between eating patterns and specific health outcomes. There is no doubt that the recommended eating patterns are associated with a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), certain types of cancers (such as colorectal and postmenopausal breast cancers), and obesity.1

Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests a relationship exists between dietary patterns and risks for some neurocognitive disorders and congenital anomalies. In fact, some authorities refer to Alzheimer’s disease as Type III Diabetes.1

What people limit in their diet is equally important, with research identifying lower intakes of meats, including processed meats and poultry; sugar-sweetened foods, and refined grains; as characteristics of healthy eating patterns.1

Second, given the lackluster consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and dairy, Americans are no strangers to nutrient insufficiencies. The lack of choline, magnesium, and vitamins A, D, E, and C creates further health concerns. Moreover, insufficient intake of calcium, potassium, dietary fiber, vitamin D, and iron (for young women of child-bearing years specifically) are considered a public health concern due to their associated health risks.1

Third, fruits and vegetables are the powerhouses for key nutrients, such as dietary fiber, potassium, folic acid, and vitamins A, C, and E.2 Additionally, they contain phytonutrients, which are naturally occurring plant-based compounds that provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition. Phytonutrients are known to protect our bodies from environmental and oxidative stress and are considered key contributors to the health benefits of whole foods and plant-based diets, such as the Mediterranean Diet.3 So when one’s diet is shy on fruits and vegetables, by default, their phytonutrient intake will suffer as well.

The 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends filling half of the plate with a variety of fruits and vegetables at every meal and snack. In particular, it promotes the regular intake of dark-green, red, and orange vegetables and beans and peas.1

So How Are We Doing?

Not so great. According to the CDC’s 2013 State Indicator Report on fruits and vegetables, adults consume fruit a scant 1.1 times per day, and vegetables a mere 1.6 times per day.4

Research on Phytonutrient Intake

Might the health benefits of phytonutrients be yet another compelling reason for people to consume their recommended servings of fruit and vegetables? Research published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics explored this issue.5

Researchers evaluated food consumption data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2003-2006, phytonutrient concentration data from US Department of Agriculture databases, and the published literature to estimate energy-adjusted usual phytonutrient intakes. They then compared phytonutrient intakes of those who consumed their recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables against those who did not. The researchers looked specifically at the intake of nine phytonutrients.5

The Results?

Not surprisingly, the energy-adjusted intakes of all phytonutrients (other than ellagic acid) were considerably higher among those who met their dietary recommendations for fruits and vegetables compared to those who did not. Unfortunately, the analysis of the more than 8,000 participants’ dietary intake revealed a lack of diversity in their fruit and vegetable choices. In fact, phytonutrient intake came from a very limited number of foods.5

The data showed an American palate for routine. For the majority of phytonutrients studied (α-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, hesperetin, and ellagic acid), just one food accounted for 64% or more of their total intake. Only a handful of foods, tomatoes, carrots, oranges and orange juice, and strawberries, accounted for approximately two-thirds or more of these five phytonutrients. For three of the remaining phytonutrients, just three foods, carrots, spinach, and onions as well as tea, contributed between 26%-31% of the average intakes.5

The Takeaway?

Based on this data, most of the American population is (over?) filling their plates with nearly everything except fruits or vegetables. Their diet is not only lacking in quality, but also diversity, which may put them at risk for nutritional insufficiencies. It also deprives them of robust phytonutrient protection against inflammation and oxidative stress.

It’s important to gradually change eating habits and adapt more of a Mediterranean way of eating. The inclusion of whole grains, legumes, fresh, seasonally grown fruits and vegetables, grass-fed meats, and omega-3-rich fish, nuts/seeds, and extra virgin olive oil rich in monounsaturated fatty acids provides protection against inflammatory conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, obesity, and certain cancers.6

In the end, how much do practitioners know about their patients’ dietary intakes? To help identify gaps in the nutrient intakes, the validated 14-item Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS) questionnaire can assess the adherence to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern and overall quality of diet and examine the associated health benefits.7

Besides, asking about diet in a focused manner sends an important lifestyle message. Doing so introduces the idea that foods, not prescriptions, may be one of the most valuable health tools. Many doctors routinely ask their patients if they buckle their seat belts. Perhaps they should consider also asking, “How many colors of the rainbow have you eaten today?”

Phytonutrients of Interest Grouped by Color—Eat the Rainbow!8

| COLOR | COMPOUND | FOOD/SOURCE | POTENTIAL BENEFIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORANGE | Beta-carotene | Carrots, orange | Neutralizes free radicals; antioxidant properties |

| Lycopene | Tomatoes, grapefruit, carrots | Neutralizes free radicals, antioxidant properties, supports maintenance of prostate health | |

| YELLOW | Cryptoxanthin | Mango, orange, grapefruit | Antioxidant, may support lung health and cellular health |

| Lutein | Mango, orange, spinach, lettuce, avocado, pear, cilantro, kiwi | Supports eye health | |

| Zeaxanthin | Spinach, kale, oranges | Supports eye health | |

| Oleanolic acid | Garlic | Cellular health and microbial balance | |

| Limonene | Oils of garlic, ginger | Cellular health | |

| Phytosterols | Almonds, sesame seeds | May reduce the risk of CHD | |

| RED, BLUE, PURPLE |

Flavonols | Supports maintenance of heart and urinary tract health | |

| Quercetin | Red onions, apples | Cardiovascular health, cellular health, and bone health | |

| Gingerol | Ginger | Cellular health | |

| Kaempferol | Strawberries, grapefruit, apples, tomatoes | Strong antioxidant, helps protect against cell damage | |

| Myricetin | Berries, walnuts | Cellular health and immune response | |

| Fisetin | Strawberries | Cognitive health | |

| Rutin | Citrus fruits, oranges, lemons, limes, grapefruit, berries, apples, tomatoes | Immune response | |

| Anthocyanidins | Raspberries, strawberries, blueberries, red apple | Antioxidant properties; may contribute to maintenance of brain function | |

| Isoflavonoid | Legumes—black beans | Supports maintenance of bone and immune health | |

| Phytoestrogens | Flax seeds, sesame seeds, berries, oat bran | Supports maintenance of heart and immune health | |

| Phenolic acids | |||

| Gallic acid | Mango, strawberries | Microbial balance | |

| Ellagic acid | Walnuts, strawberries, blackberries | Antioxidant properties, cellular health | |

| Caffeic acid | Pear, basil | May bolster cellular antioxidant defenses; may contribute to maintenance of healthy vision and heart health | |

| Ferulic acid | Oats, orange, apple | May bolster cellular antioxidant defenses; may contribute to maintenance of healthy vision and heart health | |

| Capsaicin | Chili peppers | Used in topical ointments to reduce sensation of pain, may support joint health and flexibility | |

| GREEN | Glucosinolates | Cabbage, broccoli, broccoli sprouts | Cellular health and detoxification |

| Dithiolthiones | Cruciferous vegetables-bok choy, Chinese cabbage, watercress, chard | Contributes to maintenance of healthy immune system | |

| Indoles | Cabbage, kale, garlic | Cellular health | |

| Phytic acid | Nuts, sesame seeds, beans, almonds, flaxseeds | Support for healthy lipid and glucose metabolism | |

| WHITE | Polysulfides | Garlic, onion | Supports maintenance of heart, immune and digestive health |

Resource: Higdon J, Drake JV. An Evidence-based Approach to Phytochemicals and Other Dietary Factors. 2nd Ed. New York: Thieme Publishing; 2007.

REFERENCES

1U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Study Graphic: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/chapter-2/current-eating-patterns-in-the-united-states/. Accessed November 10, 2016.

2Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S, Raymond JL. Krause’s Food and Nutrition Care Process. 13th ed. St. Luis, MO: Elsevier text; 2012.

3Higdon J, Drake JV. An Evidence-based Approach to Phytochemicals and Other Dietary Factors. 2nd Ed. New York: Thieme Publishing; 2007.

4Center for Disease Control. State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/downloads/state-indicator-report-fruits-vegetables-2013.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2017.

5Murphy MhM, Barraj LM, Herman D, Bi X, Cheatham R, Randolph RK. Phytonutrient intake by adults in the United States in relation to fruit and vegetable consumption. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(2):222-229.

6Sofi F, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a1344.

7Martínez-González MA, et al. A 14-Item Mediterranean Diet Assessment Tool and Obesity Indexes among High-Risk Subjects: The PREDIMED Trial. PLoS One. 2012; 7(8): e43134. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3419206/table/pone-0043134-t001/.

8Nutrilite Health Institute. America’s Phytonutrient Report: Quantifying the Gap. http://www.pwrnewmedia.com/2009/nutrilite90921nmr/downloads/AmerciasPhytonutrientReport.pdf.